Part 1: Representing oneself in animated documentaries:

In 2008 I left a Art Practice BA at Goldsmith’s College in disgrace. Soon afterwards my shaky mental health deteriorated and I was sectioned for drug induced psychosis brought on by cannabis abuse.

This was profoundly traumatic because I was experiencing delusions and hallucinations, while being confined for a month in a psychiatric ward whose staff practiced forceful restraint and sedation when necessary.

From 2009 to 2012 I made many animated documentaries about these experiences during my BA in Fine Art at Loughborough University. Animation seemed to be the most useful tool for processing my difficult experiences. I thought of my BA as intensive art therapy, finding that each time I crafted a narrative based on what happened I forged a more navigable path through my memory.

In addition to psychosis I experienced hypomania, a mild form of mania, marked by elation and hyperactivity. This symptom, despite not being particularly destructive or traumatic, had a strong influence on one work in particular, Ultraviolent Junglist. While not being a documentary does capture the frenetic momentum of hypomania.

WARNING – NOT SUITABLE FOR THOSE WITH PHOTO SENSITIVE EPILEPSY

Ultraviolent Jungleist (2013)

Part 2: Representing identifiable subjects in animated documentaries:

Chris Landreth was awarded an Oscar in 2004 for his documentary animation. This was characterised by Landreth as a psycho-realistic portrait of Ryan Larkin, a fallen star of the National Film Board of Canada.

Ryan (2004) Chris Landreth

I’m interested in notions of caricature and its relevance to contemporary documentary animation practice. This mode of representation is traditionally regarded as derisive, yet it is still a reasonable description of how identifiable subjects in animated documentaries are represented.

Is it fair to see Chris Landreth’s approach to representing Ryan Larkin as a caricature?

Portrait: a painting, drawing, photograph, or engraving of a person, especially one depicting only the face or head and shoulders.

Caricature: a picture, description, or imitation of a person in which certain striking characteristics are exaggerated in order to create a comic or grotesque effect.

If it is not the artist intention to be comic or grotesque is an image no longer a caricature? I would argue an audience has just as much right to make this judgement.

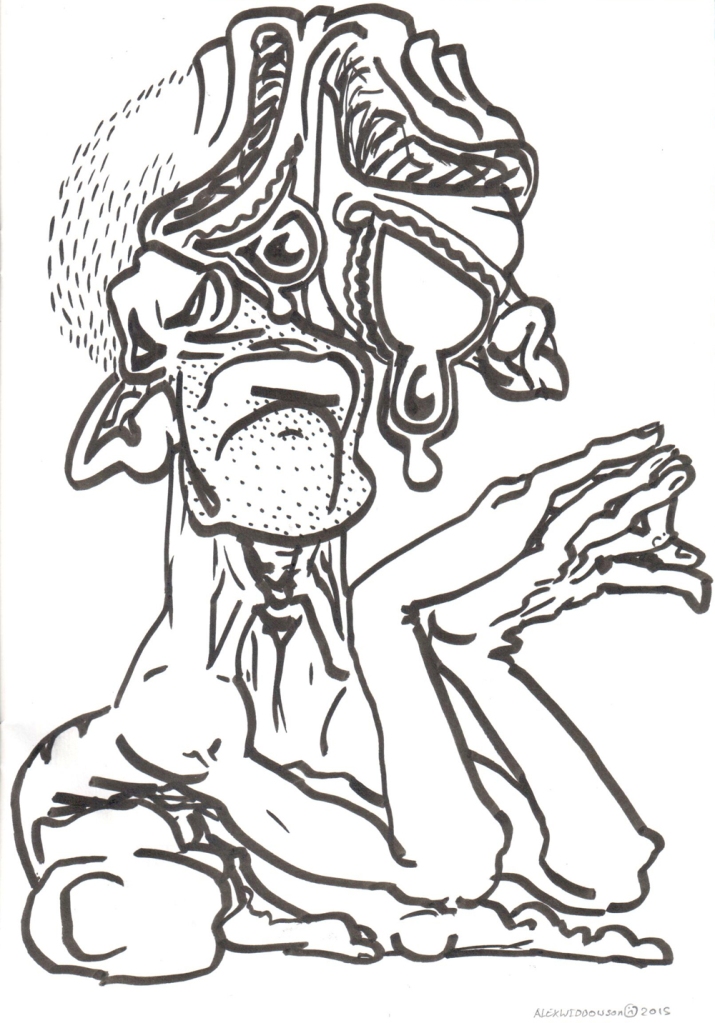

I found Ryan inspiring as an undergraduate. It essentially introduced me to animated documentary as a practice. Moreover I was drawn to the idea of ‘psycho-realism’. Since my teenage years I’d been expressing my own mixed feelings through illustrations, which contorted the male nude. I was struck with how Landreth was able to find such a convincing practical use for this type of imagery.

Sad (2015)

However, I-did-this-to-myself. Images, such as the one above, were all self-portraits, self-mutilations. Yes they were self-indulgent, but I was contorting my own image and not the face of someone I’d met, certainly not a vulnerable adult.

In contrast to the animated documentary, Ryan, the live action representation of Ryan Larkin and Chris Landreth in Alter Ego (d. Laurence Green, 2004) offers a more equal footing for the pair. Larkin is given a chance to respond to the animated film in this ‘making-of’ documentary.

Alter Ego (2004) d. Laurence Green (Start watching at 0:45:21)

Larking states:

- “I’m not very fond of my skeleton image”

- “It’s always easy to represent grotesque versions of reality”

- “I wish I could change that script”

- “I’m very nervous about being scrutinised so tightly. I just want out of this picture”

Landreth’s vision, no matter how honourable, failed to produce something that Larkin was comfortable with upon completion.

What Chris Landreth calls “psycho-realism” is also a useful term to describe Francis Bacon’s search for a raw truth in his portraiture practice. The key difference between Bacon and Landreth is that the painter acknowledges, to a degree, the inherent violence in the process of disfiguring his subject.

Francis Bacon – Fragments of a Portrait (1966) d. Michael Gill (Start watching at 0:02:29)

A significant issue with Ryan, made evident in Alter Egos, is that Landreth and Larkin seem to barely know each other. We get a sense that they’d only met a handful of times. If Ryan Larkin was offered more involvement in the film’s creation would he have felt more comfortable with how he was represented? Would Chris Landreth’s vision for the film been compromised or augmented by allowing Ryan to influence the way he was depicted?

Alter Ego only shows the moments immediately after Larkin first saw the film. I was recently informed by Shelly Page, Head of International Outreach at Dreamworks and a friend to Landreth, that Chris was still proud of film. Ryan after his initial reluctance grew to appreciate the film. It drew attention to him as an artist and reinvigorated his animation career before his death in 2007.

Christoph Steger has an incredible track record for forming trusting and collaborative relationships with the subjects of his animated documentaries. In Jeffery and the Dinosaurs, the negotiation is clear, Jeffery Marzi is offering Steger access for his low budget documentary in order to gain exposure for his screen plays.

Jeffery and the Dinosaurs (2007) d. Christoph Steger

Marzi shares his story in a relaxed and candid manner, occasionally punctuated by Steger’s modest questioning. We are given the impression of a relationship built on sensitivity and mutual respect.

Marzi’s spoken biography reveals a universal story of concern for the future, however the strange inversion of the conventional narrative of frustration and aspiration is revealing. While most of us might dream of Hollywood success, Marzi engages with that goal as part of the daily grind. Meanwhile his limitations led him to covert the reliable role of mechanic and postal worker.

I was interested in Steger’s choice to include a scene where Marzi expresses a clear misconception; the idea that J. K. Rowling’s literary success lifted her out of homelessness. Steger did not correct Jeffrey or omit the moment from the film. A director has a moral obligation to represent this subject without turning the documentary into a freak show or social pornography. Although the fear of homelessness is the driving force behind Marzi’s work, and therefore crucial to the narrative, he might have had other footage that captured this anxiety without exposing or exploiting Marzi’s naïveté.

It is possible that Steger saw the moment as crucial to the film. It feels like an honest expression of anxiety and an important moment to help audiences understand Marzi’s perspective and vulnerability. Steger may have felt it dishonest to shy away from moments like this. Would it have been patronising to omit the scene for fear of embarrassing him?

When Steger discusses the project you get a strong sense of the collaborative relationship: “I like life, and animation is almost the opposite, it’s all about fantasy. So I felt a relief to be able to have Jeffery take care of all that. He does all the imaginary work of the visuals and it’s down to me to bring them to life…. The real film for me and the artistic challenge is in the structure of the poetry, and trying to bring out those poetic moments of a story like Jeffery’s.”

I worked with Nick Mercer, an addiction therapist and former addict, in Escapology: The Art of Addiction (2016).

Despite the promise of anonymity while producing the film, Nick was proud of what we produce together and insisted on being listed in the credits.

I believe our smooth working relationship is connected to the fact that Nick and I had grown to trust one another well in advance of me making this film. In 2013 Mercer was my psychotherapist. It was a strange inversion asking him to expose his personal experiences. That therapeutic relationship lay the foundation for a trusting filmmaker/subject relationship. He’d seen my previous films and fully believed the idea of using animation to expand on his wise words.

I essentially reduced Nick down to a caricature, although the desired effect was neither comic or grotesque. I drew him many times without using photographic reference to distill my image down to a few lines. Here are some early character designs:

While I send Nick early animatics he had no desire to suggest changes. He saw my allegorical interpretations of his words as part of a 50/50 partnership to the film’s content.

My own experiences struggling with cannabis addiction as a teenager both motivated me to make this film and helped me empathise with Nick’s experience.

Part 3: Representing anonymous subjects in animated documentaries:

Lawrence Thomas Martinelli (2015) identified six motivations for creating contemporary animated documentaries:

- To integrate meta-material to visualise what is known but cannot be shown

- To manifest subjectivity

- To impress a particular point of view

- To convey emotion beyond the facts documented

- To give aesthetic stylistic expressive print to the work.

- To hide or camouflage part of the authentic footage

Performance (2016)

Currently I am developing my first year film for a brief created in partnership with the Wellcome library. I am working closely with the Philadelphia Association, for whom I am artist-in-residence, to create a documentary about their history and the PA Community Houses, places of refuge for those in mental distress. They aim to offer the true meaning of asylum. The following is a very early animation test:

Foam hand test 01 (2017)

To celebrate the launch of the new pathway in the summer of 2016 the RCA hosted the Ecstatic Truth symposium.